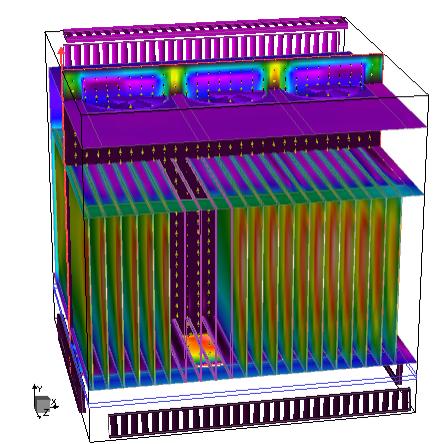

The 3.5-kW

device was designed by CAS Ltd. and built by Charlotteís Web Networks Ltd.

Having gained experience with thermal software by following the modeling tips

in this article, engineers with the companies optimized the product for

smallest size. CFD optimization in software called Coolit from Daat Research,

let the company trim the number of anticipated fans by creating the optimal

airflow in the system with judicious placement of components, boards, and

vents. All this was done without building physical prototypes.

Specialized computational fluid

dynamics or CFD software provides a wide range of capabilities for computer

prototyping of electronics in enclosures. The software lets thermal engineers

shorten design cycles, and eliminate building and testing physical prototypes.

The software also lets designers quickly and efficiently evaluate "what

if" scenarios, it simulates conditions not reproducible in a lab, and

provides more detailed information than do lab experiments. Finally, the

technology improves the operation and endurance of electronics and optimizes

placement, size, and parameters of components. In short, it helps get a design

right the first time.

CFD

technology involves solving transport equations of fluid flow and heat transfer

on computers. To solve the equations, they must be represented so computers can

handle them. This is usually done with so-called finite volume or

finite-element methods. The latter were successful only in specialized CFD

applications, such as slow flows and non-Newtonian flows. Most all production

CFD programs currently use finite-volume methods and we will refer only to

them.

Putting

the latest CFD technology to best use takes practice and a few unavoidable

mistakes. The problems here are solved with software called Coolit from Daat

Research and the following guidelines have been compiled from observations of

new users. Learning from their mistakes may shorten your learning curve.

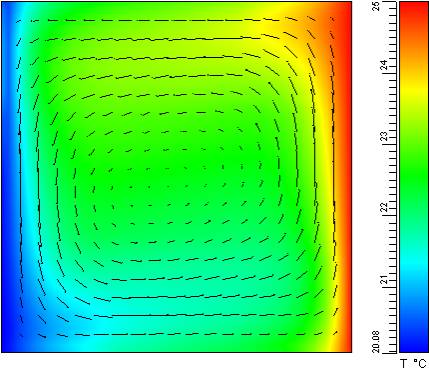

Start with simple models.

Gain confidence in your modeling abilities and the softwareís capability, start

with simple problems, and compare results to analytical solutions and

experimental data. One of the easiest problems to set up includes laminar

natural convection in a square cavity with vertical heated walls and adiabatic

conditions at top and bottom.

The

problem should take a few minutes to set up and even less to solve.† A solution to this problem appears in the

accompanying illustration Flow in a

square cavity. The same problem can be slightly modified to obtain another

well-researched solution of turbulent natural convection in a rectangular

cavity.

To get familiar with the

software and build confidence in its use, work on simple well-documented models

such as the flow in a square cavity with heated walls.

Finding

out how your numerical solution stacks up against the real world is easy with these

examples because readily available reliable data makes for an easy comparison.

If you experimented with the model by setting different grids and convergence

criteria, you noticed the solution changed along with the parameters.

Determining a sufficient grid

for an accurate numerical solution means finding the coarsest grid or mesh that

provides good answers. This discussion applies both to unstructured and

structured grid systems. In general, a finer grid produces more accurate

solutions than a coarser one on the same models. In mathematical terms, the

numerical solution will tend to the solution of the underlying partial

differential equations as the grid is refined.

In

practice, however, a uniform grid refinement for 3D problems is virtually impossible

as the total number of grids grows exponentially. For instance, if a model has n = 70 grid cells in each direction,

increasing the number by only 10% will increase the total number of grid cells

33% from 343,000 to 456,533. Increasing n

by 50% in each direction expands the grid to over a million cells for a 238%

growth.

Another simple

but important problem is the backward-facing step flow. In fact, every obstacle

in the path of airflow is a backward-facing step. Many experimental and

numerical results are available for comparison.

Fortunately,

the solution error depends on both the total number of grid cells and their

distribution. Correctly distributed grids go a long way toward getting an

accurate solution. A simple example illustrates the point. Consider an

exponentially fast varying boundary layer, which is obtained as a result of

solving a convection diffusion equation:

Solving

this problem on uniform grid with R=10

produces 14% maximum error when 10 cells are used in the boundary layer. To

reduce that error to less than 5%, at least 100 uniform grid cells are needed

in the boundary layer.

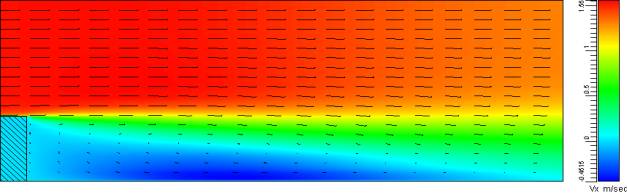

The image is an example of a

laminar temperature boundary layer developing on a flat plate. Itís another

important problem because itís encountered frequently, itís easy to set up, and

solutions are readily available.

A

better way to reduce the error is to use non-uniform grids, with smaller cells

towards the wall, where the solution changes rapidly. In the case of the

boundary layer, an optimum solution uses a logarithmic distribution of grids.

Such grid will yield the exact solution with only two cells in the boundary layer!

Obtaining

exact solutions on specially designed grids is not an easy feat for general 3D

problems. Sufficiently accurate grids, however, are possible. Software, such as

Coolit, will automatically produce grids optimized in that regard.

But

the question still remains: In the absence of experimental data, how can one

determine a sufficient grid? The only method is to recompute the same problem

on finer grid and compare results. When the solution in the points of interest

does not appreciably change, the previous grid was sufficient. Otherwise,

youíll need to repeat the process until changes to the solution become small.

Define the simulationís goal before you

start modeling.†

A goal could be to reduce the number of fans, keep the temperature of a

particular package or component within limits, or select a heat sink.

Objectives change as projects progress.

Use

coarse grid simulations to determine the sensitivity of design decisions on

critical components, such as fan parameters or placement. The same applies to

optimization problems that require comparing different designs to find a best

one. This case would call for examining relative rather than absolute numbers.

If an objective is to determine heat-transfer coefficients on the surface of an

enclosure, there is no need to specify internal details. The only important

element is the position and power of heat sources. The accuracy of a predicted

heat transfer coefficient would not be affected.

Do a triage on your CAD model.

In most cases, one cannot simply press a button and move a CAD model to thermal

software. Too much detail overwhelms computers without a corresponding

improvement in accuracy. Simplify the model by deciding what is important in

the simulation.

For

example, consider an enclosure with several pin fin heat sinks, each with 11x11

pins. A coarse grid - about two grid cells per pin, three per space between the

pins, and 20 cells in the direction normal to the base - requires 500,000 grid

cells. Add other components and you quickly run out of computer resources.

Ask

if the model needs an accurate solution everywhere, or only in certain parts of

the model. Be realistic. Greater accuracy requires more time to build a more

detailed model and finer grid with correspondingly longer solution times.

Itís

worth the effort to trade unneeded detail in a model for a shorter solution

time. With regard to pin-fin heat sinks, when itís critical to find a solution

around only one sink, then replace the other two with lumped-parameter

versions, such as a porous media model available in most CFD codes. The effect

of the lumped-parameter heat sinks on the rest of the problem should be close

to that of the detailed model, so the solution around the important sink is not

adversely affected. Donít forget that partially converged solutions are one way

to quickly check a model setup for its accuracy. A complex model usually takes

considerable time to reach a fully converged solution, and a mistake in the

setup wastes that time. Instead, solve the problem for a few iterations

and look at results. Recognizing modeling errors early allows correcting them

before the case converges. You may, for example, see that a component is

unexpectedly hot - a good indicator that you mistyped its power dissipation or

thermal conductivity value. Or, check the fan curves when a flow seems too

fast. Itís a good idea to use this technique every time you start a complex

model.

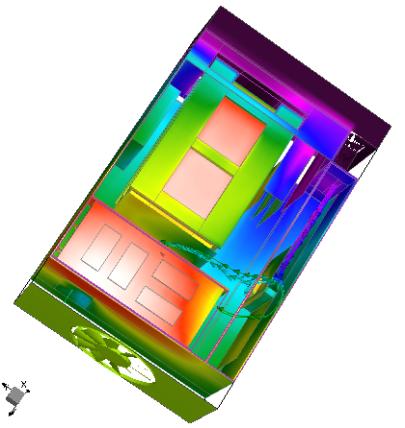

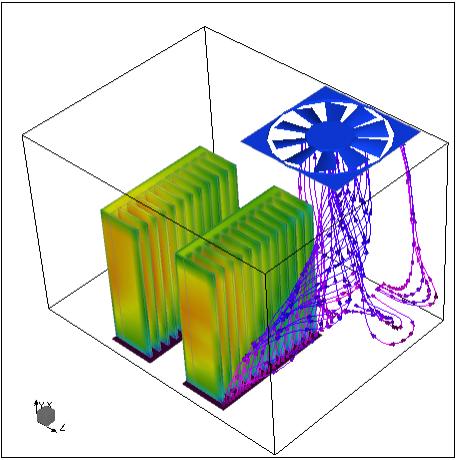

The avionics equipment built

by Miltope Corp. Boulder, CO, was also optimized using CFD software. The model

used several lumped parameter submodels and successfully predicted temperatures

of critical components to within a few degrees.

The heat sinks look similar but analysis with CFD

software showed that one is 50% less efficient than the other. Reports

accompanying the analysis further detail the study with quantitative

information.†

Use a coarse-grid solution when faced

with optimization or sensitivity studies. Looking for an

optimum component arrangement usually requires comparing several different designs

to determine their relative performance. Coarse-grid analysis is the perfect

tool for the task. It allows quickly and efficiently predicting whether one

design is better than another. NEC engineers, for example, used the method to

quickly determine that a heat sink from one manufacturer is 50% less effective

than a similar one from another.

Sensitivity

studies with coarse grids make sense when you donít have all the information to

build a CFD model, or when some of the information is suspect. It becomes

important to determine whether or not the suspect quantity appreciably affects

the prediction of critical parameters. When it turns out the missing data is

unimportant, the analyses can safely continue using estimates.

The

same approach works when itís necessary to determine sensitivity to lumped

parameter models. After replacing a component or a group with their simplified

versions, it is important to determine how the change affects critical parts.

Coarse-grid analyses let users judge whether important components in the model

are sensitive to the parameters selected for the lumped parameter model.

Check the mass and energy balance

using hand-calculated estimates. Itís a good way to see whether or not a CFD

model has gross errors. Do the mass and energy balances hold? Does the order of

magnitude predicted using hand-calculations and numerical simulations agree? If

any of these are not true, look for an error in the setup or the model.

Identify turbulence.

All CFD programs require that users specify whether the flow is turbulent or

laminar before doing the simulation and, if the flow is defined as turbulent,

require you select a turbulence model. (Turbulence models are approximations of

the original equations that allow simulations on regular grids.) Turbulence

models are necessary because even though the CFD governing equations correctly

capture turbulence, very fine grids are required to do so accurately. This

approach of modeling turbulence on fine grids is called a direct simulation and

is used primarily in academia for basic research.

Selecting

the right type of flow is important because assuming laminar flow instead of

turbulent may significantly under-predict heat transfer. Robust turbulent eddy

mixing results in the effective thermal conductivity in electronics

applications ten to hundred times greater than it is for laminar flow.

Many

commercial CFD codes provide on-line advice based on specified boundary

conditions. But the advice is often misleading. For example, one suggestion

says when a system has a fan, flow is turbulent. That is indeed true next to

the fan. The question is whether the flow is still turbulent as it goes through

the rack of closely spaced PCBs carrying heat-sensitive components. It probably

is not. Most of the airflow will bypass the rack along paths with less

resistance. And whatever goes through the rack becomes laminar as the flow

squeezes in the narrow passageways between boards.

Using

a turbulence model with wall functions is likely to over-predict the amount of

heat transfer from the board. That means the model will predict lower than

actual temperatures for board components. A better choice is to avoid the

turbulence model or use advanced turbulence models without wall functions,

which work reasonably well in both the laminar and turbulent regions of the

flow.

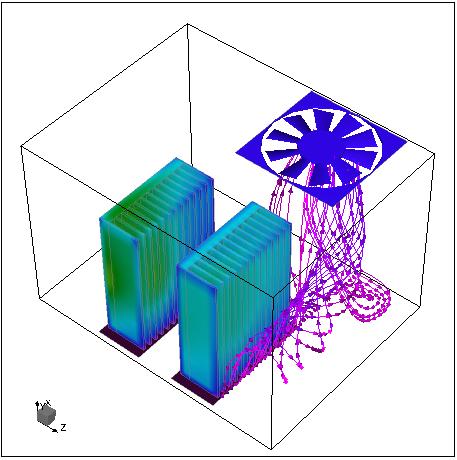

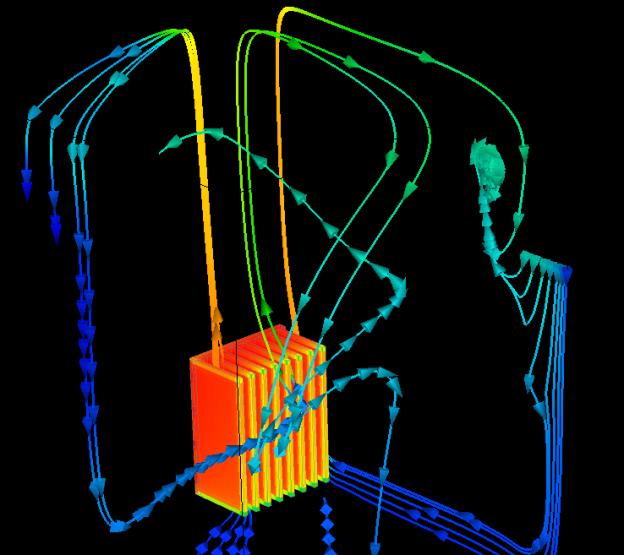

The simulation for an electronics equipment

manufacturer was computed using a turbulence model in Coolit that is capable of

modeling mixed flows. It correctly predicts transition of flow from highly

turbulent (white) to laminar (violet) and again to turbulent.

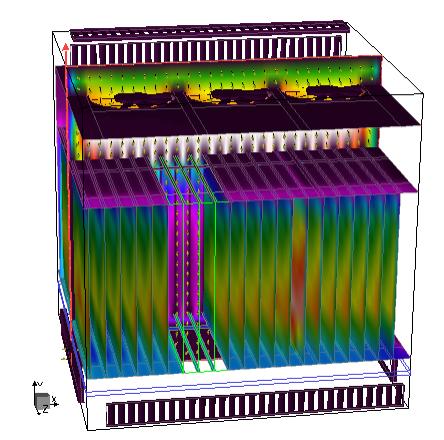

A

special case is free convection flows that have no steady state solution. For

example, in the flow shown below, the air plume at the point of impact where

the rising warm air hits the ceiling of the enclosure oscillates. You wonít be

able to find a steady state solution to this laminar flow problem. The solution

residuals, that measure the departure of solution from steady state after

reaching a plateau oscillate with the flow. Users have several options after

recognizing that the plumeís oscillations have almost no effect on the

temperature of the plate fin below:. accept the solution with oscillating

residuals as ďconvergedĒ; use a turbulence model without wall functions to

dampen the oscillations and obtain a steady state solution, or solve the

problem as time-dependent, obtain results over a period, and average them. All

three approaches are legitimate and produce similar results. But unless you are

writing a scientific paper, the third approach is not practical because it

takes a lot longer than the other methods.

Coolit simulation of the Nokia benchmark

experiment in which a rising plume oscillates.